Turkey is located between the rich hydrocarbon reserves in the Caspian region and the European markets and thus sits at the intersection of the most feasible energy transit lines. Yet, geopolitics is not the only reason why Turkey is relevant to the EU’s energy interests in the Caspian. Turkey also has significant political capital and economic ties in the Caspian region that the EU can capitalize on to achieve its long-term energy policy objectives.

Despite the fact that the EU and Turkey have a shared interest in energy security, there are at least two major obstacles that have so far prevented the EU and Turkey from effectively coordinating on energy policy. First, the dissimilar and at times incompatible energy interests of the EU members undermine the EU’s capacity to implement a common external energy policy. Unable to speak in one voice, the EU sends mixed signals to its regional partners, including Turkey. Similarly, Turkey tends to prioritize its own short-term national energy interests over the long-term benefits from cooperation with the EU. The prevalence of national interests over communal ones thus generates a credible commitment problem between the EU and Turkey, where parties are unable to make binding promises for cooperation. For the EU and Turkey to establish a working partnership on energy issues, they should arrive at a common understanding whereby each actor not only values long-term cooperation over short-term interests but also trusts that the other side will do the same. Second, the commitment issue is aggravated by the apparently mismatched perspectives that the EU and Turkey adopt on the political implications of energy cooperation. Turkish decision makers hold that Turkey’s position as an energy corridor merits tangible political benefits, most notably concrete progress in Turkey’s accession talks. Even though most EU officials acknowledge that Turkey could be a strategic asset for European energy security, few go so far as to establish a direct issue-linkage between energy and membership. The discordance of the EU’s and Turkey’s expectations regarding the political payoffs of energy cooperation undermines the mutual trust that is required for long-term partnership.

The EaP was introduced as a joint Polish-Swedish initiative in May 2008. The initiative was conceived as a venue for dialogue and cooperation between the EU and the former Soviet states of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. The Joint Declaration of the Prague Eastern Partnership Summit, signed on 7 May 2009, stated that the “main goal of the Eastern Partnership is to create the necessary conditions to accelerate political association and further economic integration between the European and interested partner countries” (European Union, 2009). Through the implementation of Association Agreements, the EaP aims to facilitate the social, economic, and political transformation in the six partner states.

The EaP is a multi-dimensional directive, yet energy security has been at the core of the partnership since its inception. The Prague Declaration says, “The eastern partnership aims to strengthen energy security through cooperation with regard to long term stable and secure energy supply and transit, including through better regulation, energy efficiency and more use of renewable energy sources” (European Union, 2009). Energy security is one of the four thematic platforms of the EaP, along with democracy and good governance, economic integration and contacts with people. Two of the six flagship initiatives of the EaP are also energy-related. One of these initiatives concerns the integration of regional energy markets and raising the profile of renewable energy in partner states, whereas the other initiative directly involves the diversification of energy import routes. On 8 May 2009, the very next day following the EaP Summit, the Southern Corridor Summit was held in Prague, where European Commission officials as well as the presidents of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, expressed their “political support to the realization of the Southern Corridor as an important and mutually beneficial initiative” (EU at the UN, 2009). Jose Manuel Barroso, President of the European Commission, speaking at the summit, underlined that diversification was indeed a priority: “The context of this summit is very clear. Our strategic priority in the EU is to enhance energy security in particular by diversifying the EU’s energy sources and energy routes”.

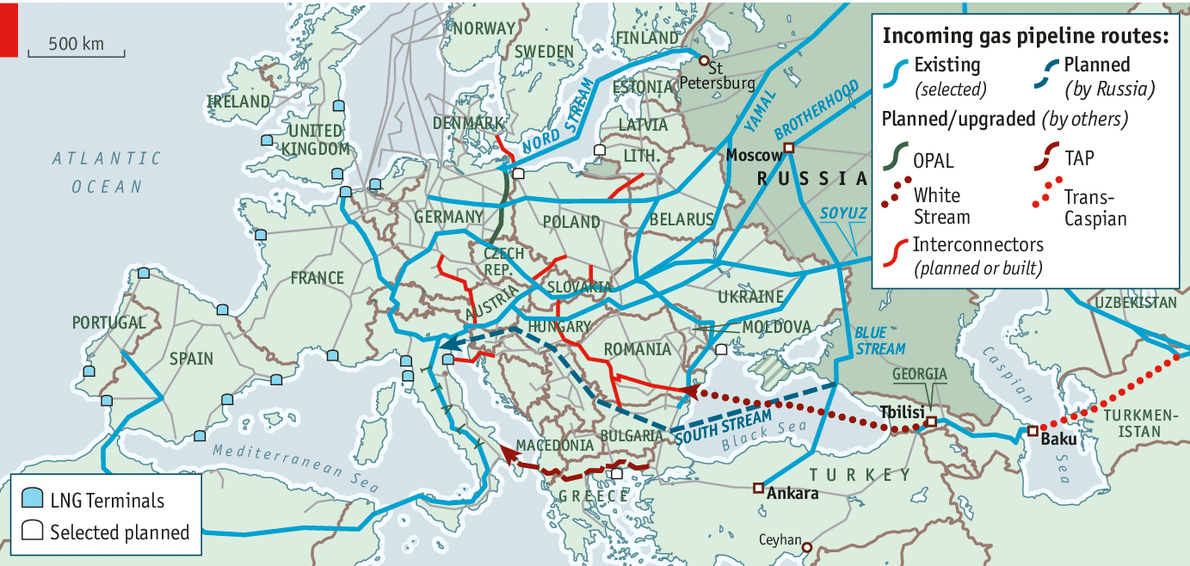

At the core of the EU’s diversification strategy is the development and integration of multiple pipeline systems under the general framework of the Southern Gas Corridor, which would carry gas to Europe primarily from the Caspian region (possibly from Turkmenistan, Iran, and the Middle East as well), bypassing transit networks owned or controlled by Russia. This grand energy strategy can be traced back to the establishment of INOGATE (Interstate Oil and Gas transport to Europe) in 1995. INOGATE was later expanded through the signing of umbrella agreements in 2001 when 21 countries agreed to cooperate on pipeline development. Through conferences in Baku in 2004 and in Astana in 2006, INOGATE evolved into the primary institutional framework of regional cooperation on energy security and integration of markets. The next major step in building the institutional framework of a European energy policy was the signing of Energy Community Treaty, which entered into force in July 2006, establishing an Energy Community among the EU members as well as Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, Macedonia, Serbia, Moldova, and Ukraine. Yet another landmark was the Treaty of Lisbon in 2007, which included an article on energy policy, calling for solidarity among Member States. In February 2010, the European Commission established a new DirectorateGeneral for Energy, further indicating the significance attached to the issue. The EaP’s energy agenda should thus be considered the latest step in the evolution of EU’s long-standing efforts to resolve the energy security problem.

How severe is the energy security problem of the EU? Europe is an energy-poor region. It possesses only 0.4 per cent of the world’s proved oil reserves but consumes 15.9 per cent. Similarly, 0.9 per cent of world’s natural gas reserves are in Europe while European consumption constitutes 13.9 per cent of the global consumption (BP, 2012). Not only are the hydrocarbon reserves limited but also production is falling. Total energy production in the EU declined by 13 per cent over the last 20 years. Natural gas production in Europe is in decline. Since 2001, EU-28’s natural gas production decreased by 38 per cent while consumption was reduced by only about 7 per cent. This unfavorable supply and demand structure inevitably led to greater import dependency. Europe’s total energy import dependency rose from 47.1 per cent in 2001 to 53.4 per cent in 2012. Europe imports 90 per cent of its oil and 42 per cent of its solid fuels, yet gas dependency is the most alarming. Gas import dependency jumped from 48.8 per cent in 2001 to 65.8 per cent in 2012 (Eurostat, 2014).

EU is following a multifaceted energy security strategy (European Commission, 2014a,b). The union is committed to reducing primary energy consumption by 20 per cent by 2020 (European Commission, 2011). The energy saving measures are helpful but ultimately insufficient to compensate for the decline in production. In 2012, natural gas consumption in Europe declined 9.9 per cent while production fell by 11.4 per cent. It is possible that part of the decline in energy consumption over the past few years is due to the contraction of the European economy since 2008. With economic restoration over the next decade, energy demand will likely increase, unless policy changes produce significant changes in the structure of energy consumption.

Indeed, projections for EU’s natural gas demand for the two decades indicate significant variations based on policy environment and expectations regarding macro-economic performance. According to Eurogas’ Base Case, which assumes no significant departure from current policy and market conditions, EU-27’s natural gas demand will increase from 438 mtoe (million tonnes of oil equivalent) in 2010 to 471 mtoe in 2035 (Eurogas, 2013, p. 3) In the Environmental Case, which assumes a growing share of renewables and a restoration of economic growth in Europe, demand for natural gas will rise to 527 mtoe by 2035, a 20 per cent increase over the 2010 baseline. Only under the Slow Developments Case, which assumes that gas would become less competitive in Europe, will demand decline to 394 mtoe by 2035 (Eurogas, 2013, p. 3). Thus, barring a significant change in policy and market conditions, natural gas will likely remain a key source of energy for Europe over the next two decades.

Similarly, a report published by Fitch Ratings in August 2014 confirmed that Europe will continue to depend on Russian gas supplies “for at least the next decade and potentially much longer” (Fitch Ratings, 2014). According to Fitch Rating’s projections, European gas demand will grow slightly until the mid-2020s and after that, demand growth will once again accelerate as gas-fired electricity generation replaces coal and nuclear capacity. European shale gas, the report indicates, will not be a viable option for another decade when production reaches a critical volume. Even then, shale gas production would most likely be just enough to compensate for the decline in domestic conventional gas production in Europe. The best the EU can hope for, the report concludes, is to avoid significantly increasing gas purchases from Russia. (Fitch Ratings, 2014).

Thus, energy import dependency will likely continue to be a major issue for Europe. Dependency, particularly on a single supplier, is considered a source of economic and political vulnerability in international relations (Waltz, 1970). Dependent countries are highly vulnerable to supply disruptions whether they are of technical or political nature. The 2006 and 2009 gas shortages in Ukraine and 2007 crisis involving Belarus served as bitter reminders that import dependency threatens the material well-being and security of ordinary citizens. Import dependency has negative consequences on the foreign policy capabilities of the dependent country as well. The potential cost of aggravating an energy supplier casts the dependent actor into an involuntarily cooperative role. Foreign policy implications of energy dependency are particularly relevant when the energy exporters are keen on using their market power as a weapon over importers and transit countries (Gereben, 2013; Stegen, 2011). Ukraine Crisis in 2014 evidenced the extent to which energy dependence constrains EU foreign policy.

Given the political and economic costs of energy dependency, the EU has no choice but to seek to diversify its energy suppliers and import routes. The EU has a few alternative natural gas suppliers, including Iraq, Iran and most recently Eastern Mediterranean but none of these alternatives appears to be as readily accessible as the Caspian reserves in the near future. Iraqi natural gas reserves rank 12th in the world (EIA, 2013) but given various infrastructure issues and the continuing political turmoil in the country, Iraq’s natural gas export capacity is currently limited. Importing natural gas from Iran has long been on the agenda of the EU and the most recent problems with the availability of Russian gas have once again brought the issue to the forefront (The Telegraph, 2014). Most European countries are looking forward to the normalization of relations with Tehran, as evidenced most recently by UK’s plans to reopen its embassy in Tehran (Foreign & Commonwealth Office, 2014). With a treasury badly damaged by the international sanctions, Iran too would be most interested in selling its gas to Europe, arguably more so than selling to Pakistan (Forbes, 2014). While Iranian natural gas reserves, estimated to be the second largest in the world, constitute a viable alternative for Europe, accessing these reserves poses a challenge in the short term. Even if the ongoing negotiations between P5+1 and Iran ultimately succeed in lifting the sanctions on Iranian energy trade, Iran’s South Pars gas reserves require significant development and investment over the next decade. Once developed and rendered available for international trade, Iranian natural gas will likely be transported to Europe via the proposed Persian Pipeline (Iran-Europe pipeline) or possibly a re-animated Nabucco pipeline, both of which are projected to pass through Turkey. Recently discovered gas in the Eastern Mediterranean would also be a welcome addition to Europe’s energy portfolio yet given the disputes over maritime borders in the region (Eissler & Arasıl, 2014), the enduring Cyprus problem and the diminishing of hostilities between Turkey and Israel since the escalation of Turkey-Russia border spat on downing of latter’s Su-24 in Syria (in 2015), it is getting quite clear that Eastern Mediterranean gas may be available for European consumptionin a significant quantities in the future. Though, fingers are crossed.

Given the various political and economic limitations of bringing online the natural gas from Iraq, Iran and the East Mediterranean in the near term, the Caspian region—estimated to hold six per cent of the world’s proven reserves and well-endowed with foreign investment—currently appears to be the most politically and economically feasible option for European diversification strategy.

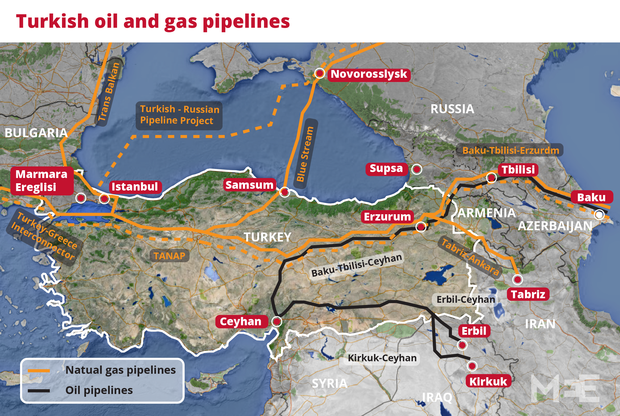

The Southern Gas Corridor linking Caspian reserves to European markets consists of several existing and projected pipelines. The Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum (BTE) gas pipeline carries gas from Shah Deniz gas field in the Azerbaijani sector of the Caspian Sea to Turkey since late 2006. The current capacity of the pipeline is 8 bcma (billion cubic meters per annum) but with the completion of the phase II of the Shah Deniz project it can be scaled up to 25 bcma. BTE currently supplies Georgia and Turkey but it can be linked to other projects like the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) which will initially carry about 16 bcma of gas from Georgian-Turkish border to Turkish-European border. Depending on the gas flow, the capacity of the pipeline can later be increased up to 60 bcma.

There are several options to further transport the Caspian gas from Turkish territory to European markets. The primary existing route is the Turkey-Greece Inter-connector, which carries up to 12 bcma of natural gas. A key aspect of this project is the extension across Greece to Italy, which will carry Caspian gas deeper into Europe. A few additional routes to transport Caspian gas from Turkey to Europe have been considered. Nabucco West, the revised version of the defunct Nabucco project, was planned to start from the Turkish-Bulgarian border and transport gas from Shah Deniz Gas field phase II via Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary to Austria. Yet Shah Deniz Consortium partners rejected Nabucco West in 2013 and opted for the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) instead. The main supply source of TAP will be the gas extracted from phase II of the Shah Deniz field, which will be carried through Turkish territory via BTE and TANAP. TAP is planned to start at Greece, cross Albania and the Adriatic to reach Italy.

Turkey thus sits at the intersection of the pipelines that constitute the Southern Gas Corridor. Turkey’s relevance to the EU’s energy policy with respect to Eastern Partnership, however, is not limited to Turkey’s fortunate geopolitical position. Secure and reliable access to Caspian hydrocarbon reserves requires not only a network of pipelines but also regional political stability and cooperation between supplier and transit states. Turkey, with its long-standing economic ties in the Caspian region can potentially act as an intermediary between the EU and the partner countries. Turkey has also been willing to contribute to the resolution of the several “frozen conflicts” throughout the region by acting as an interlocutor between the EU and other relevant parties.

Ankara has a standing policy of promoting interdependence among the three South Caucasus states in order to expand their trade and energy ties with Turkey. Georgia is not only a transit corridor of Azerbaijan’s gas, but also a major trade route for Turkish exports to Central Asia. Turkey also has considerable investments in Azerbaijan, Georgian and Abkhazian economies. Pending on the normalization of relations with Armenia and the opening of the Turkish-Armenian border, economic relations with Armenia also hold great promise for Turkey. Turkey can also help the EU in its capacity building efforts in the Caspian region. Turkish state-owned energy companies TPAO and BOTAS are partners in many pipeline projects in the region. Turkey has also recently shown a great deal of interest in investing in upstream development projects in the region. TPAO for instance signed in May 2014 a 1.5 billion USD deal to acquire French Total’s 10 per cent stake in Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz project. In addition to Shah Deniz, TPAO owns shares in the two major fields in Azerbaijan, ACG (6.75 %) and Alov (9 %). Turkey has a strong presence on the ground and Turkish private sector accumulated expertise that is critical for secure and long-term cooperation.

Lastly, Turkey due to its historic ties to the region has considerable political capital in the Caspian, particularly in Azerbaijan, with which Turkey has sustained a very close relationship since its independence. Turkey also cooperated with the US in its efforts to help Georgia build a new state after independence. Given the difficulties that the EU has experienced in politically reaching out to its Caspian partners over the last decade, the EU can benefit from Turkey’s role as a regional interlocutor between Europe and the Caspian partners.

It is evident that the EU and Turkey can both benefit from extending their cooperation on regional energy issues. Despite the commonality of interests, however, EU-Turkey energy cooperation has so far failed to meet mutual expectations. The next section examines how the prevalence of national interests over communal ones and the opposing views on the Turkish and European sides regarding the political implications of energy partnership undermine the ability of these two actors to commit to a more extended form of energy cooperation.

About The Author:

Tolga Demiryol is assistant professor of Political Science in the School of Economics and Administrative Sciences at Istanbul Kemerburgaz University in Turkey. Tolga Demiryol received his Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Virginia in 2010. Dr. Demiryol specializes in international political economy and security. His recent research focuses on the geopolitics of energy.

Publication Details:

Baltic Journal of European Studies. Volume 4, Issue 2, Pages 50–68, ISSN (Online) 2228-0596, DOI: 10.2478/bjes-2014-0015, November 2014

This work is an abstract form of author’s original work, titled “The Eastern Partnership and the EU-Turkey Energy Relations”which is licensed under Creative Commons 3.0

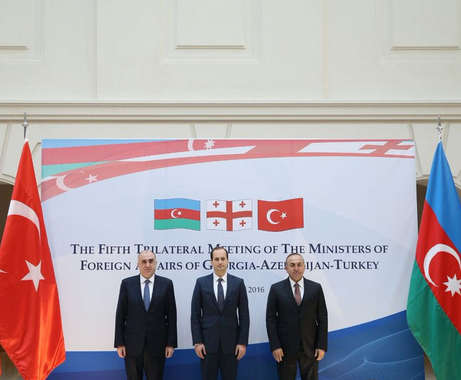

Tbilisi is hosting a trilateral meeting of Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Elmar Mammadyarov, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu and Georgian Foreign Minister Mikhail Janelidze.

Tbilisi is hosting a trilateral meeting of Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Elmar Mammadyarov, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu and Georgian Foreign Minister Mikhail Janelidze.