New study: Nord Stream 2 will benefit security of gas supply in Europe

Nord Stream 2 is likely to benefit rather than hurt energy security in Central and Eastern Europe and in the UK and Germany. The gas pipeline, which Gazprom and five major Western European energy companies want to build from Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea, can only be credibly stopped by the EU if the European Commission decides to transform itself from a “powerful competition watchdog” to a “political actor. Those are some of the main conclusions of a new study written by Andreas Goldthau for the European Centre for Energy and Resource Security (EUCERS) and the Russia Institute of King’s College London published today.

Nord Stream 2 is likely to benefit rather than hurt energy security in Central and Eastern Europe and in the UK and Germany. The gas pipeline, which Gazprom and five major Western European energy companies want to build from Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea, can only be credibly stopped by the EU if the European Commission decides to transform itself from a “powerful competition watchdog” to a “political actor. Those are some of the main conclusions of a new study written by Andreas Goldthau for the European Centre for Energy and Resource Security (EUCERS) and the Russia Institute of King’s College London published today.

“Nord Stream 2 will enhance the liquidity of Central European gas hubs in EU gas trading and pricing, and strengthen their role as continental price markers.” This is one of the key conclusions Dr Andreas Goldthau, a Fellow with King’s Russia Institute and Professor of Public Policy at Central European University, draws in the EUCERS report, “Assessing Nord Stream 2: regulation, geopolitics and energy security in the EU, Central Eastern Europe and the UK” (11 July).

Both the European Commission and Central and Eastern European countries strongly resist the pipeline project precisely because they argue it will undermine energy security in their region. Nord Stream 2 is intended by Gazprom to bypass Eastern Europe to end Russian dependence on transit through the region, in particular through Ukraine. This will lessen the importance of Eastern Europe in the European gas market and make it even more dependent on Russian gas than is currently the case, so opponents of the pipeline argue.

Prime ministers

Goldthau takes a different perspective. It should be mentioned at the outset that Goldthau’s report was financed by the five Western European partners – Shell, BASF/Wintershall, Uniper, OMV and Engie – that each hold 10% in the project. His analysis may be said to reflect at least implicitly the vision of these companies, which have been strongly criticized by Nord Stream 2’s opponents for supporting a project that they say undermines solidarity in the EU energy market.

In October last year, Miguel Arias Cañete, Commissioner of Climate Action and Energy, said there were were “serious doubts” whether Nord Stream 2 was compatible with the EU’s “strategy of security of supply”, one the main pillars of the Energy Union. Diversification of routes and sources is key to this strategy and “Nord Stream 2 does not follow this core policy objective”, said Cañete.

Nord Stream 2 “might in fact end up making Russian gas compete with Russian gas … The overall net effect might therefore be consumer benefit.”

On 17 March 2016, Prime Ministers and leaders of 9 EU member states (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovak Republic, Romania, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Croatia) sent a letter to Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, arguing that Nord Stream 2 poses “risks for energy security in the region of Central and Eastern Europe, which is still highly dependent on a single source of energy”.

At an event on 6 April in Brussels, Maros Šefčovič, Vice-President of the European Commission in charge of the Energy Union, said that “Nord Stream 2 could alter the landscape of the EU’s gas market while not giving access to a new source of supply or a new supplier, and further increasing excess capacity from Russia to the EU.” MEP and former Polish Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek of the European People’s Party (Christian-Democrats), said at the same event that “Nord Stream 2 and Energy Union cannot co-exist”.

Lowest prices

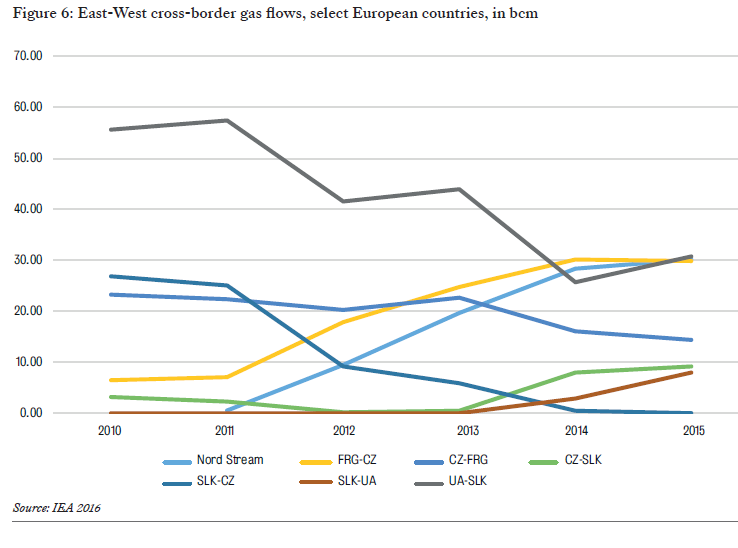

Goldthau puts forward a very different view. First of all he points out that the first Nord Stream pipeline, built in 2011 – it runs along the same route and is owned by Gazprom (51%), Gasunie, Eon, Wintershall and Engie – was resisted for the same reasons, but it had an opposite effect than what had been expected: “particularly in Central Eastern European markets (…) significant shifts happened in the aftermath of Nord Stream coming online. (…) gas flows started to reverse (see figure 6). While traditional gas would travel from East (Russia) to West (transiting Ukraine / Belarus and feeding Slovakia /Poland), West-to-East trade picked up.”

The additional volumes brought by Nord Stream in combination with enhanced reverse flow infrastructure capacity between Germany and Austria and its Eastern neighbors, contractual changes and “the Commission putting an end on market barriers such as destination clauses” led to these shifts in European gas trade. These “regional markets [in Central and Eastern Europe] were not only connected physically, but arguably also linked to more liquid market areas in North-Western Europe”, writes Goldthau.

“Energy sector governance in South Eastern Europe remains poor. Regulatory uncertainty is high, transparency in policy making remains low, and so is capacity in public administration”

The EU, writes Goldthau, with its three energy market packages, especially the Third Energy Package (2009), which enforced third-party access provisions on pipeline infrastructure through ownership unbundling and established independent regulator, created liberalised gas markets. It further integrated these markets by building pipeline interconnections and reverse flow capacity, a process that is still going on. According to Goldthau, gas supplied through Nord Stream enters this market and thereby increases liquidity rather than dependence on a single supplier.

He notes that gas prices in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) “started to align with German prices. (…) Compared to the ‘traditional’ situation in which prices of gas tended to be higher in Eastern Europe than in Western Europe, a function of rigid long-term contract structures and a lack of optionality, this amounts to a qualitative shift in CEE gas prices. This ties into the more general finding that competitive, integrated and hub based markets tend to have the lowest gas sourcing prices in the EU, notably the UK, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany. By contrast, countries lacking the physical interconnection and lagging behind in implementing pertinent EU regulation, tend to have persistently high import prices in the EU, notably in South Eastern Europe and in the past also the Baltics.”

Consumer benefit

Goldthau writes that Nord Stream 2 may be expected to further reinforce this effect on the gas market: “Nord Stream 2 stands the chance of enhancing the liquidity of regional hubs in which the additional volumes of 55 bcm will be primarily absorbed. This includes GASPOOL [in Germany] and by extension the Central European Gas Hub (CEGH) [in Austria] via EUGAL [the proposed online extension of Nord Stream 2 to the German-Czech border] and the Czech and Slovak grids, but also NetConnect Germany (NCG).”

This, adds, Goldthau “will strengthen the role of regional Central European gas hubs in EU gas trading and pricing. Current ‘transit hubs’ such as CEGH will be upgraded to become (…) full-fledged ‘trading hubs’ such as TTF [in the Netherlands] and NBP [in the UK].”

“It is particularly East European member states that have been most reluctant to embrace cross-country gas market integration as a means to enhance European supply security and overall market resilience against supply shocks”

As happened with the first Nord Stream, Nord Stream 2 “might in fact end up making Russian gas compete with Russian gas”, i.e. with gas that comes from Russia via Ukraine and Eastern Europe. “The overall net effect might therefore be consumer benefit. To be sure, as the example of the UK demonstrates, the development of an integrated (regional) market and a functioning and liquid hub is a matter of decades rather than years. Moreover, its precondition is physical infrastructure, transparency and political willingness, which clearly is not present among some CEE countries and their political leadership. But the main point is that contrary to the prevalent debate about Nord Stream 2 putting in question CEE energy security, chances are that it might have the opposite effect.”

Reforms rolled back

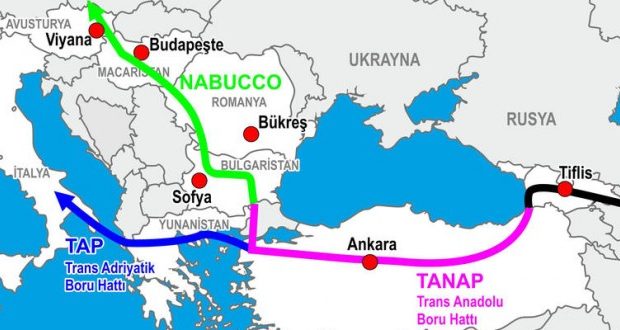

Goldthau admits that further on into South Eastern Europe (SEE) problems of security of supply do persist. But the main reason for this is “slow progress in energy sector reform coupled with lagging infrastructure development. This is, per se, not a problem linked to Nord Stream 2, nor caused by Nord Stream 2.”

The author points out that “energy sector governance in SEE remains poor. Regulatory uncertainty is high, transparency in policy making remains low, and so is capacity in public administration. Various infringement procedures in SEE EU-member states drive home the point that European policy frameworks are not properly implemented, if at all. Incumbent monopoly companies – (…) a case in point being Bulgaria’s Bulgargaz – tend to defend the status quo and prevent competition from emerging, while regulated prices prevent market signals from exerting effects. In some instances, market reforms are even rolled back, such as in Hungary where the energy sector was recently re-nationalized.”

He concludes that overall for Europe supply security is not at stake, unless it is interpreted only in terms of “diversified routes and suppliers”, which is the lens through which Eastern European leaders and the European Commission tend to use when they look at dependency on Russia. According to Goldthau, this is not a reasonable view to take: “if market logic is applied, which is exactly what the EU energy market project is all about, then energy security is primarily enhanced through competition policy and structural market changes as they help keeping dominant market players such as Gazprom in check and foster price competition.”

“Put in simple terms: the Commission’s job is not the choose pipeline routes, but to ensure they are operated in a way that is compatible with market principles”

According to Goldthau, the EU’s “primary policy objective” should be “harmonizing market rules and functioning, liberalizing and connecting so far still scattered national markets, in addition to fostering diversification of sources to enhance choice.” Yet, “it is particularly East European member states that have been most reluctant to embrace cross-country gas market integration as a means to enhance European supply security and overall market resilience against supply shocks.”

Goldthau thus puts the ball back in the court of the Eastern Europen countries, which he says do not do enough to foster competition and would like to retain the ‘easy money’ they earn by Russian gas transit: “While some countries such as Poland carefully safeguard the prerogatives of state-owned corporations, others such as Hungary recently re-nationalized the gas sector altogether. This ties into material interests of some incumbent East European (state) companies to keep the status quo, and the revenue streams from existing long-term contracts – in addition to Slovak or Polish governments remaining naturally interested in additional state revenue in the shape of transit fees. The result is an incentive to keep the status quo, i.e. Yamal Europe and the Ukrainian transmission system in operation.”

Pivotal supplier

Goldthau does concede that although Nord Stream 2 may increase liquidity, the source of the gas that will enter the market will still be Russia. “Gazprom will be the pivotal supplier on CEE regional gas hubs, which – depending on the strategy Gazprom adopts – may translate into market power. The concern here is if Gazprom decides to play the market game, this could give the company market leverage in the shape of volume management. Indeed, its market share of presently a good third of European gas demand – which in Central Eastern Europe is significantly higher – coupled with its control over gas storage facilities, might hand Gazprom an opportunity to tinker with supply volumes in order to influence prices.”

But he argues that this kind of threat should be addressed through competition regulation: “The primary argument against such concerns is that the idea of gas market integration is precisely to deprive dominant suppliers of their ability to leverage their position on consumers. Moreover, it is somewhat ironic to warn against Gazprom’s strategic positioning in a market environment as ‘playing by EU market rules’ is exactly what has been demanded of Gazprom for years.”

The Energy Union clearly represents an attempt to react to geopolitical shifts in the European neighborhood and a more assertive Russia … It certainly envisages the use of the entire regulatory toolbox at EU level in a more strategic and more targeted way

As to Ukraine, it is true that this will country will lose some €2 billion in transit fees per year, but it will also benefit from lower gas prices. “Put simply, Ukraine might essentially trade a situation in which it accrues high transit fees but pays high prices for Russian gas for a situation in which transit revenues are small but coupled with lower expenses for gas imports.13 Because the trade-off primarily benefits households and industry, financial benefits are in the long run shifted to consumers.”

The last point is important, since the transit fees in the past tended to benefit a small group of corrupt stakeholders in Ukraine. According to Goldthau, “a back on the envelope calculation suggests that while the net effect for Ukraine might not be neutral it still looks far better than what the commonly cited figure of as loss of $2 billion a year suggests. In fact, based on 2015 numbers, the country might have already saved up to roughly $ 1.15 billion due to competitive pricing pressures.”

Political aims

Goldthau notes that “it is the declared intention of EU leaders to keep Ukraine a transit state for Russian gas”, but that this “is an EU policy goal whose primary motivation is stabilize the Ukrainian leadership’s domestic and foreign policy position, and to tie the country more closely to the EU through a strategic energy partnership. Achieving this policy goal, however, also implies that it is politics, not regulation or EU infrastructure policy that needs to drive the process.”

This relates to a key question Goldthau throws up, based on his analysis. Should the EU confine its role to ensuring that the energy market functions well or should it pursue political aims throug the energy market? Goldthau believes the EU’s role should be limited: “Put in simple terms: the Commission’s job is not the choose pipeline routes, but to ensure they are operated in a way that is compatible with market principles. Politics, by contrast, defines policy preferences. If Nord Stream 2 is politically too contested or found as undesirable, then it also falls on the political domain – the EU heads of states – to act.”

“Whilst the objectives of the Energy Union do not have legal character, the European Council decision suggests that they now define the broader political context in which EU regulation should be put to operation”

In this context, Goldthau raises another key issue – about the idea of Energy Union itself. Is this an economic or primarily political concept? How does it relate to the idea of a liberal integrated energy market? “To be sure, it is unlikely that the EU will develop a monopsony in natural gas which at the very end runs counter to EU market principles. Nor will the Energy Union do away with the liberal market paradigm the EU is built on. Yet the Energy Union clearly represents an attempt to react to geopolitical shifts in the European neighborhood and a more assertive Russia, the bloc’s key energy suppliers. It certainly envisages the use of the entire regulatory toolbox at EU level in a more strategic and more targeted way, toward external actors, with a view to serving the goal of ensuring ‘energy security, solidarity and trust’.”

He adds that “in this context it is worth noting that the European Council – the EU heads of states – in their December 2015 declaration clearly stated that ‘Any new infrastructure should entirely comply with the Third Energy Package and other applicable EU legislation as well as the objectives of the Energy Union’. This not only signals support for a potentially tough stance adopted by the Commission. It also elevates the Energy Union objectives to political guidelines for regulation as applied. The Energy Union (…) defines energy security and a Strategic Partnership on energy with Ukraine as key goals for the EU. Whilst the objectives of the Energy Union do not have legal character, the European Council decision suggests that they now define the broader political context in which EU regulation should be put to operation.”

Goldthau calls on EU actors to make a clear choice. If they are opposed to Nord Stream 2 and want to stop it entirely, they can only do so credibly on geopolitical grounds. If they merely object to Nord Stream 2 because of the effects it might have on the gas market, they should address those market imperfections, not to try to stop the pipeline.