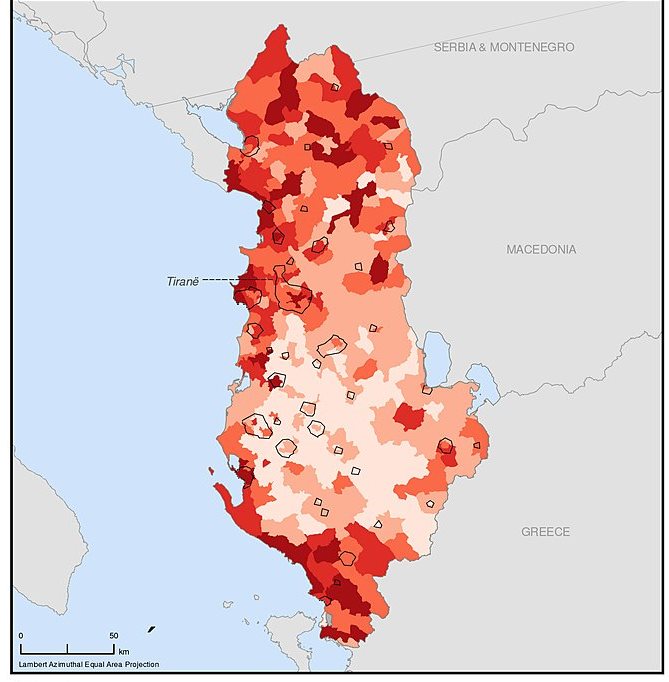

Coastal flood risk in Albania

Vulnerabilities – Coastal flood risk in Albania

Vulnerabilities – Coastal flood risk in Albania

A sea level rise is projected up to 24 cm by 2050 and up to 61 cm by 2100. This will result in the gradual inundation of low lying coastal areas. The natural communities associated with such areas are expected to move inland (1).

In non-protected lagoons, accretion is expected to occur, following destruction of the low strands separating them from the sea. The formation of new wetlands is expected in Mati (1).

The population living in coastal areas, particularly in beach areas, is seriously threatened by the expected increase, in the sea level. Houses, hotels, roads and agricultural areas etc., situated in the lower zones of the Adriatic coastal line (excluding the territories under the effect of raising movements), will be flooded (1).

The beaches in the areas affected by land subsidence (those of Shëngjin, Kune-Vain, Tale, Patok, Ishëm), and a substantial number of fields (drained in the late 50’s and early 60’s.) will be swept over by floods. Likewise, these floods will find their way into important segments of the local and national roads (including a part of the new road Fushë Krujë-Lezhë running through the former Lac swamp land), potable water supply sources (located in Lezha and Lac plains), as well as many lodging and tourism structures which have been, and continue to be built along these beaches. Also, the floods will partially affect the beaches situated in the territories undergoing elevation (those of Durrës, Golem, Divjakë, Himarë, Borsh etc.), in addition to the tourism infrastructure (1).

The same lot is expected to affect the agricultural land (in the former swamps of Durrës, Myzeqe, Narta, Vrug etc.) as well as dwelling centers and rural infrastructure, which reach up to 50 cm above the sea level (1).

Global sea level rise

Observations

In their fourth assessment report the IPCC reported that there was high confidence that the rate of observed sea level rise increased from the 19th to the 20th century (2). They also reported that the global mean sea level rose at an average rate of 1.7 (1.2 to 2.2) mm yr-1 over the 20th century, 1.8 (1.3 to 2.3) mm yr-1 over 1961 to 2003, and at a rate of 3.1 (2.4 to 3.8) mm yr-1 over 1993 to 2003.

According to satellite altimetry-based data anthropogenic global warming has resulted in global mean sea-level rise of 3.3 ± 0.4 mm/year over the period 1994-2011 (8). According to a recent study, however, this previous estimate of global mean sea level rise is too high and global sea level rise over the period 1993 to mid-2014 has been between +2.6 ± 0.4 mm/year and +2.9 ± 0.4 mm/year (10). According to this same study sea-level rise is accelerating; this acceleration is in reasonable agreement with an accelerating contribution from the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets over this period (12,13), and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projections (12,14) of acceleration in sea-level rise during the early decades of the twenty-first century of about +0.07 mm/year. Sea-level rise varies from year to year, however, due to short-term natural climate variability (especially the effect of El Niño–Southern Oscillation) (8,11): the global mean sea level was reported to have dropped 5 mm due to the 2010/2011 La Niña and have recovered in 1 year (11).

Updated satellite data to 2010 show that satellite-measured sea levels continue to rise at a rate close to that of the upper range of the IPCC projections (3). Whether the faster rate of increase during the latter period reflects decadal variability or an increase in the longer-term trend is not clear. However, there is evidence that the contribution to sea level due to mass loss from Greenland and Antarctica is accelerating (4).

Projections

For 2081-2100 compared to 1986-2005, projected global mean sea level rises (metres) are in the range (9):

- 0.29-0.55 (for scenario RCP2.6)

- 0.36-0.63 (for scenario RCP4.5)

- 0.37-0.64 (for scenario RCP6.0) and

- 0.48-0.82 (for scenario RCP8.5)

Extreme water levels – Global trends

More recent studies provide additional evidence that trends in extreme coastal high water across the globe reflect the increases in mean sea level (5), suggesting that mean sea level rise rather than changes in storminess are largely contributing to this increase (although data are sparse in many regions and this lowers the confidence in this assessment). It is therefore considered likely that sea level rise has led to a change in extreme coastal high water levels. It is likely that there has been an anthropogenic influence on increasing extreme coastal high water levels via mean sea level contributions. While changes in storminess may contribute to changes in sea level extremes, the limited geographical coverage of studies to date and the uncertainties associated with storminess changes overall mean that a general assessment of the effects of storminess changes on storm surge is not possible at this time.

On the basis of studies of observed trends in extreme coastal high water levels it is very likely that mean sea level rise will contribute to upward trends in the future.

Extreme waves – Future trends along the Mediterranean coast

Recent regional studies provide evidence for projected future declines in extreme wave height in the Mediterranean Sea (6). However, considerable variation in projections can arise from the different climate models and scenarios used to force wave models, which lowers the confidence in the projections (7).

References

The references below are cited in full in a separate map ‘References’. Please click here if you are looking for the full references for Albania.

- Republic of Albania, Ministry of Environment (2002)

- Bindoff et al. (2007), in: IPCC (2012)

- Church and White (2011), in: IPCC (2012)

- Velicogna (2009); Rignot et al. (2011); Sørensen et al. (2011), all in: IPCC (2012)

- Marcos et al. (2009); Haigh et al. (2010); Menendez and Woodworth (2010), all in: IPCC (2012)

- Lionello et al. (2008), in: IPCC (2012)

- IPCC (2012)

- Cazenave et al. (2014)

- IPCC (2014)

- Watson et al. (2015)

- Yi et al. (2015)

- Church et al. (2013), in: Watson et al. (2015)

- Shepherd et al. (2012), in: Watson et al. (2015)

- Church et al. (2013), in: Watson et al. (2015)