Gjatë viteve të fundit, dëshmojmë një përkeqësim të rëndë të marrëdhënieve energjitike, ndërmjet Rusisë dhe Bashkimit Evropian (BE-së). Çështja mbi gazin, është një çështje tepër e rëndësishme, e lidhur ngushtë me përpjekjet e vazhdueshme nga ana e Rusisë për të ri-kalibruar strategjinë e gazsjellësit Euro-aziatik, si dhe orvatjet nga ana tjetër e BE-së për krijuar rrugë të reja furnizimi. Rajoni i Detit Kaspik, tashmë është shndërruar në pikën kyçe të këtyre diskutimeve të nxehta, në fazën e mosmarrëveshjeve serioze, ndërmjet Rusisë dhe BE-së. Ndërkohë që, Azerbaixhani dhe Turkmenistani konsiderohen si partnerë jetik të mundshëm të konsumatorëve Evropian të energjisë, Rusia angazhohet me politikat e saj më agresive, në mbrojtje të interesave të saj kombëtare në rajon. Rivaliteti i vazhdueshëm Rusi- BE, mbi projektet alternative të furnizimit me gaz, jo vetëm që e thellon boshllëkun e marrëdhënieve Bruksel-Moskë, por gjithashtu ka përcjellë ndikimin e saj, ndaj strategjive mbi energjinë të vendeve Kaspike, duke u përpjekur të mos shndërrohet në një fushë-beteje ndërmjet dy aktorëve kryesor.

Gjatë viteve të fundit, dëshmojmë një përkeqësim të rëndë të marrëdhënieve energjitike, ndërmjet Rusisë dhe Bashkimit Evropian (BE-së). Çështja mbi gazin, është një çështje tepër e rëndësishme, e lidhur ngushtë me përpjekjet e vazhdueshme nga ana e Rusisë për të ri-kalibruar strategjinë e gazsjellësit Euro-aziatik, si dhe orvatjet nga ana tjetër e BE-së për krijuar rrugë të reja furnizimi. Rajoni i Detit Kaspik, tashmë është shndërruar në pikën kyçe të këtyre diskutimeve të nxehta, në fazën e mosmarrëveshjeve serioze, ndërmjet Rusisë dhe BE-së. Ndërkohë që, Azerbaixhani dhe Turkmenistani konsiderohen si partnerë jetik të mundshëm të konsumatorëve Evropian të energjisë, Rusia angazhohet me politikat e saj më agresive, në mbrojtje të interesave të saj kombëtare në rajon. Rivaliteti i vazhdueshëm Rusi- BE, mbi projektet alternative të furnizimit me gaz, jo vetëm që e thellon boshllëkun e marrëdhënieve Bruksel-Moskë, por gjithashtu ka përcjellë ndikimin e saj, ndaj strategjive mbi energjinë të vendeve Kaspike, duke u përpjekur të mos shndërrohet në një fushë-beteje ndërmjet dy aktorëve kryesor.

Konflikti i vazhdueshëm në Ukraninë, si dhe shqetësimet e ngritura, lidhur me sigurinë e furnizuesve të gazit Rus drejt tregut Evropian, kanë përshkallëzuar tensionet ndërmjet Rusisë dhe BE-së, duke arritur nivelin e tyre më të lartë në këto vitet e fundit. Natyra bashkëkohore e marrëdhënieve BE-Rusi mbi energjinë, është rezultati i një kombinimi të ndërlikuar faktorësh gjeopolitikë dhe ekonomikë, të cilët janë të lidhur, ngushtësisht me përfitime të mëdha dhe sigurinë kombëtare. Në thelb të mosmarrëveshjeve aktuale mbi energjinë është një konkurrencë e fortë për qiradhënien e burimeve, ndërmjet prodhuesve të energjisë, konsumatorëve dhe vendeve tranzite ku tek kjo e fundit përfshihet edhe Shqipëria. Ndërlikimet gjeopolitike, aksesi ndaj tregut, modernizimi ekonomik dhe sovraniteti kombëtar, janë disa ndër çështjet kyçe, të cilat kanë ndikuar në politizimin e marrëdhënieve BE-Rusi. Në vijimësi të vënies së sanksioneve nga Perëndimi kundër Rusisë, marrëdhëniet mbi energjinë janë bërë edhe më të ngurta, duke mbyllur të gjitha rrugët e mundshme për të rifituar besimin e humbur nga të dyja palët.

Megjithëse, si Brukseli dhe Moska e kanë mbështetur zyrtarisht de-politizimin e çështjeve mbi energjinë, të dyja palët kanë këndvështrime të kundërta, sesi sektori duhet të organizohet në tërësi. BE-ja kërkon të integrojë Rusinë në sistemin e tregut, ndërkohë që Moska refuzon politikat e vlerave Evropiane, si dhe kundërshton regjimin ekzistues ndërkombëtar të tregtisë energjitike. Nxjerrja e sanksioneve kundër Rusisë, ka rezultuar, si rrjedhojë në një sfidë për politik-bërësit Evropian. Gjithësesi, qasjet e ndryshme dhe interesat kontradiktore, i kanë vënë si Rusinë dhe BE-në përpara rrezikut të konfrontimit, e cila ka gjasa të përçojë një ndikim negativ, lidhur me sigurinë e sektorit energjitik për të dy palët.

Realitetet Aktuale të Bllokimit të Energjisë BE- Rusi

BE-ja, duke qenë se është e përfshirë në liberalizimin e tregut energjitik, aktualisht është duke u përballur me një hendek serioz, ndërmjet zvogëlimit të burimeve vendase dhe kërkesës në rritje të energjisë. Megjithëse, BE-ja përpiqet të promovojë tregtinë e lirë të energjisë përtej kufijve të saj, politikat Evropiane mbi energjitikën mbizotërohen nga interesat kombëtare, duke penguar krijimin e një qëndrim të përbashkët dhe të orientuar strategjikisht ndaj BE-së lidhur me organizimin e tregut energjitik.

Deri më tani, interesat brenda BE-së i kanë penguar Vendet Anëtare, për të formuluar një politikë kohezive dhe të integruar mbi energjinë. Nga ana tjetër, Rusia, ka ndjekur një qasje të ndryshme, lidhur me globalizimin e tregut energjitik, duke kundështuar rolin vetëm të një eksportuesi të thjeshtë të energjisë. Politikat mbi energjinë të zhvilluara nga Rusia, dominohen nga objektivat kyçe strategjik, lidhur me trendet e gjeopolitikës dhe ekonomisë globale, si dhe ndryshimet sociale dhe politike. Kremlini paraqet fuqimisht forcën e tij gjeopolitike, dhe shpesh përdor metoda të ashpra, me qëllim garantimin e interesave strategjik Rus. Megjithatë, mundësia e një rivaliteti vijon të jetë i lartë, për shkak se projektet kryesor mbi investimet dhe rrugët e tubacioneve gazsjellës, kanë ndryshuar ndjeshëm pozicionet ekzistuese të pushtetit.

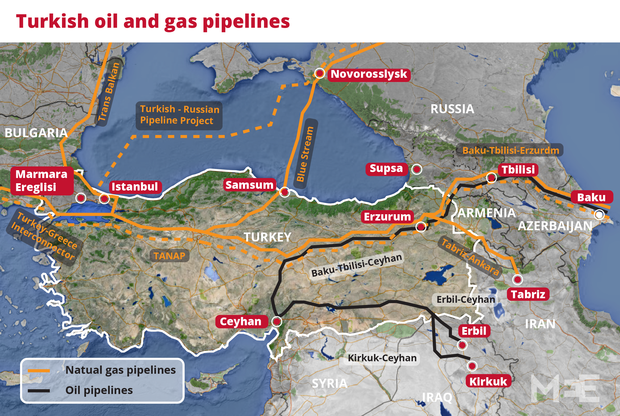

Qysh prej nisjes së krizës në Ukrainë, drejtuesit e Kremlinit, e kanë rishikuar dukshëm strategjinë mbi tubacionet e gazit të Rusisë. Ndërkohë që, Rusia dominon tregjet e energjisë Evropiane prej mëse shumë vitesh, strategjia e energjisë Ruse, ka pasur ndikimin e saj mbi shumë shtete Evropiane dhe jo-Evropiane, në lidhje me kërkesën, furnizimin dhe tranzitin. Rrugë të reja alternative për gazin dhe naftën, janë gjithësesi jetike për Moskën. Në këtë kuadër, Rusia drejtohet nga Azia, aty ku bashkëpunimi energjitik me Kinën, dukshëm është intensifikuar gjatë viteve të fundit, duke sjellë sfida të reja për konsumatorët Evropian. Me qëllim rivendosjen e statusit të super-fuqisë, Presidenti Vladimir Putin, është i përqëndruar në përdorimin e burimeve natyrale të pamata në vend. Vizioni i ri i Kremlinit, lidhur me tregun global të energjisë, është të rrisë vetë-besimin Rus, nëpërmjet një sërë alternativash të mundshme në Euro-azi.

Nga ana tjetër BE-ja, është duke bërë çdo përpjekje, për të zvogëluar varësinë e saj ndaj Rusisë, duke shumëfishuar burimet e saj të furnizimit me gaz natyral. Megjithëse, disa alternativa janë duke u marrë aktualisht në konsidertë ndaj furnizuesit Rus të gazit, ka shumë pak gjasa që BE-ja të zvogëlojë dukshëm importet e saj të energjisë nga Rusia, në një të ardhme të afërt. Vetë fakti, që Rusia zotëron furnizuesit më të mëdhenj të energjisë në aspektin global dhe tashmë ka një infrastrukturë domethënëse në vend, e shpjegon shumë qartë, pse disa prej kompanive më të mëdha të energjisë në Evropë, ngurrojnë të zhvendosen tërësisht nga status quo-ja. Nuk është çudi, pse këta të fundit kanë interesa të larta financiare, për të mbajtur një furnizim të qëndrueshm të gazit nga Rusia. Megjithatë, BE-ja po përpiqet që të zhvillojë projekte të reja alternative mbi energjinë. Furnizimi me gaz natyral për në tregun Evropian nga rajoni i detit Kaspik dhe në një kohë tjetër zonat gas mbajtëse të Iranit, janë parë për një kohë të gjatë si qëllimi i BE-së, ndaj një përpjekje për të lehtësuar ndopak varësinë Ruse.

Pjesët kryesore të Enigmës Kaspike

Vendet Anëtare të BE-së e kanë njohur rëndësinë gjeopolitike të gjirit Kaspik, duke konsideruar Azerbaixhanin dhe Turkmenistanin si një korridor strategjik, i cili lidh Evropën jugore me Kaukazin dhe Azinë Qendrore.Ndërkohë që jemi në dijeni, të potencialit të pasur që ofrohet nga burimet hidrokarbure të Kaspikut, BE-ja ka realizuar në të njëjtën kohë projekte me investime të reja, të cilat do të ndikojnë në sigurinë dhe qëndrueshmërinë e furnizuesve botëror të energjisë në të ardhmen. Mëse e vërtetë, tashmë që, Azerbaixhani dhe Turkmenistani janë shndëruar në palët kyçe të rajonit të Kaspikut dhe të dy vendet zënë një vend të veçantë në strategjinë e BE-së, lidhur me shumëllojshmërinë e furnizimit me gaz.

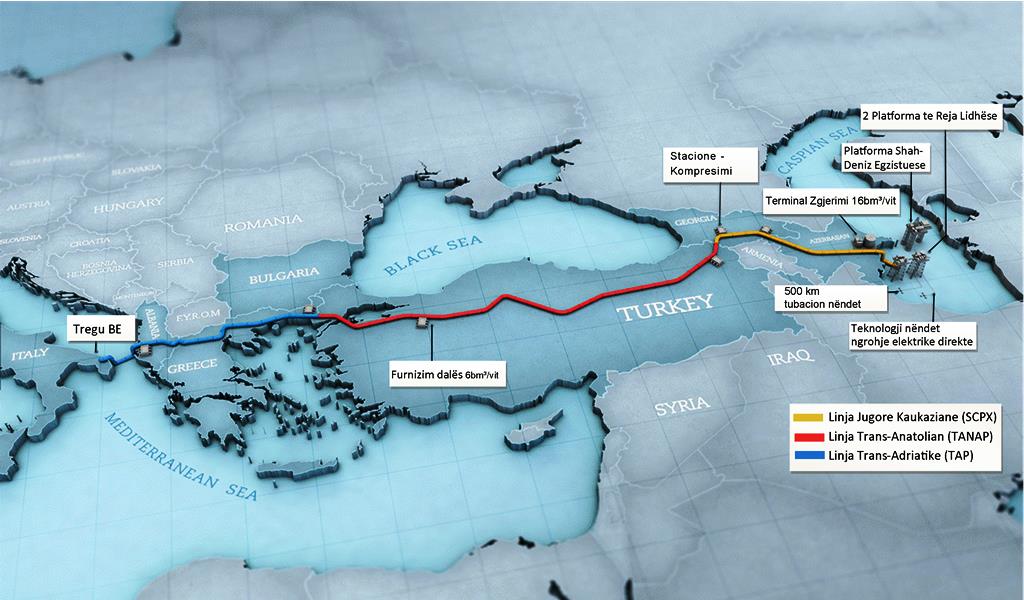

Brukseli ka rritur marrëdhëniet me Bakun dhe Ashgabatin, me qëllim aksesin ndaj depozitave të energjisë në Detin Kaspik dhe zvogëlimin e varësisë së Evropës, ndaj importeve të energjisë Ruse. Në vijimësi, BE-ja ka nisur bisedime të drejtpërdrejta mbi projekte ndërkombëtare, të cilat do të mundësojnë furnizimin e konsiderueshëm të energjisë nga gjiri Kaspik drejt tregut Evropian. Gazsjellësi Trans-Anatolian (TANAP) dhe gazësjellësi Trans-Adriatik (TAP) si rezultat, do të japin Korridorin e Gazit Jugor kaq të dëshiruar, e ashtuquajtura si “Rruga e Re e Fildishtë”, për linjat e transportit të energjisë, ndërmjet gjirit Kaspik dhe BE-së. Sapo kjo lidhje jetësore, të fillojë zbatimin në dekadën e ardhshme, do të mundësojë ndaj BE-së importin e gazit natyral nga Azerbaixhani, Turkmenistani dhe mundësisht nga Irani. Përveç kësaj, Brukseli ka nisur një fushtë aktive prapagande për projektin e tubacioneve të gazsjellësit Trans-Kaspik, e i ri-prezantaur kohët e fundit në axhendën e BE-së, për çështjet e energjisë. Tubacioni Trans-Kaspik, do të jetë pjesë e projektit TANAP, i cili është duke u ndërtuar nga Azerbaixhani dhe Turqia. Me shumë gjasa, tubacioni Trans-Kaspik, do të thellojë më tepër aksin lindje-perëndim të marrëdhënieve mbi energjinë, ndërmjet Azerbaixhanit, Gjeorgjisë, Turkmenistanit, Turqisë dhe Vendeve Anëtare në BE.

Pavarësisht kësaj, energjia mbetet një ndër sfidat kryesore për Azerbaixhanin dhe Turkmenistanin, lidhur me politikat vëndase dhe të jashtme, jo vetëm ndaj BE-së, por edhe ndaj vëndeve të tjera, veçanërisht Rusisë. Rrjedhja e plotë e gazit Kaspik në Evropë, parashikon një qëndrueshmëri në këto dy vende, veçanërisht e parë në planin afat-mesëm. Proçeset vendimmarrëse si në Baku dhe Ashgabat(Turkmenistan), shpesh lidhen me zgjidhjen e ekuacioneve rajonale të gjeo-politikës dhe gjeo-ekonomisë. Në realitet, rrugët e tubacioneve TANAP, TAP dhe Trans-Kaspik, janë projekte me risk zero. Disa prej çështjeve të mundshme, lidhur me këto projekte, përfshijnë risqet që kanë të bëjnë më furnizimin, ndërtimin, statusin ligjor të Detit Kaspik dhe çështjet mjedisore, të cilat tashmë janë diskutuar nga ana e Moskës dhe Teheranit.

Furnizimi me gaz natyror, duke rritur ndërvarësinë midis furnitorëve dhe konsumatorëve, e shndërron situatën politikisht më të ndjeshme. Eksporti i burimeve hidrokarbureve nga Deti Kaspik ndaj Evropës, si rezultat do të sfidohet ndaj faktorëve të veçantë, si për shembull interesat gjeo-politke të fqinjve të fuqishëm, duke konkurruar projektet e tubacioneve të gazit, ndryshimet lidhur me rrugët e furnizimit dhe problemet teknike. Për shembull, pengesa kryesore e TAP-it nuk është shtyrja e datës së inagurimit të këtij projekti me një vit më shumë, deri në 2021, por janë kushtet e reja, të cilat janë shtruar në tavolinë nga qeveria Greke.

Direkt pas zgjedhjeve, kryeministri Grek Alexis Tsipras, nisi të fliste për politikat e tubacioneve të gazit. Më 3 shkurt 2015, Greqia deklaroi se do të mbështeste ndërtimin e tubacioneve të TAP-it, përgjatë gjithë territorit të saj, por përfitimet që do t’i sillte Athinës, mund të ishin të pamjaftueshme dhe nisën diskutimet për t’u rishikuar. Në vijim të njoftimit për fillimin e Turkish Stream, Greqia e gjen veten në një pozicion gjeografik strategjik, lidhur me garantimin e energjisë ndaj BE-së. Që atëherë, të dyja tubacionet e gazsjellësit (TAP dhe Turkish Stream) kanë nisur garën, se cila do të ishte e para për të kaluar nga Turqia në Greqi, duke përfituar avantazhet. Në të vërtetë, Tsipras është duke përdorur kartën e tij të fortë, ndaj sigurisë së energjisë në BE. Ai po përdor pozicionin gjeografik të Greqisë, për të vendosur një tarifë më të lartë për TAP-in, megjithëse marrëveshjet nga ri-negociatat do të shkaktojnë hatërmbetje tek qeveria e tij.

Në të njëjtën kohë, projekti i tubacionit të gazsjellësit Trans-Kaspik mund të jetë i zbatueshëm, vetëm nëse Azerbaixhani dhe Turkmenistani do të shfaqin dëshirën për të irrituar Moskën. Kjo varët nga aftësia e të dy vendeve, për t’i rezistuar presionit që mund të vijë nga çdo drejtim, veçanërisht nga Rusia dhe Irani, të cilët në mënyrë të vazhdueshme kanë ngritur për diskutim statusin e pazgjidhshëm të Detit Kaspik, me arsyetimin se ndërtimi i gazsjellësit do të dëmtojë mjedisin e Detit Kaspik.

Gjatë shqyrtimit të politikave shumëdimensionale mbi energjinë, Baku dhe Ashgabat kanë marrë gjithë masat ndaj një sfide me interes të ekulibruar, duke shmangur në të gjitha mënyrat çdo lloj konflikti të drejtpërdrejtë me Mokën, në lidhje me materializimin e Korridorit të Gazit Jugor. Nisur edhe nga shqetësimet politike, as presidenti i Azerbaixhanit Ilham Aliyev dhe as Presidenti i Turkmenistanit Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, nuk mund të ushtrojnë presion më të fortë, sesa ai i ushtruar nga BE-ja, në lidhje me rrugën e tubacionit gazjellës Trans-Kaspik-TAP-TANAP. Të dy Baku dhe Ashgabat janë gati të nisin me implementimin e projektit, por nuk po shohin mbështetjen e mjaftueshme politike, nga ana e BE-së dhe kanë dyshimet, në lidhje me gatishmërinë e BE-së për të kundështuar Moskën, në lidhje me zbatimin e këtyre nismave ndërkombëtare. Si rrjedhojë, efekti i presionit të madh të ushtruar nga Rusia, varet në mënyrë direkte nga rezistenca e frontit të bashkuar të BE-së.

Në mënyrë paradoksale, BE-ja po përpiqet të krijojë një union mbi energjinë, i cili ka për qëllim, miratimin e sa më shumë marrëveshjeve transparente mbi gazin, me qëllim zbehjen e ndikimit Rus. Pavarësisht angazhimeve të fuqishme për të arritur krijimin e një tregu të përbashët energjie, BE-ja deri më tash nuk ka arritur të mundësojë një zgjidhje gjithëpërfshirëse ndaj shumicës së interesave kombëtare konfliktual të Vendeve Anëtare. Për më tepër, mungesa e një integrimi fleksibël, aq shumë të nevojshëm në tregun Evropian të energjisë, i ka dhënë Rusisë më tepër hapësirë për të mavoruar ndaj politikave të tubacioneve gazsjellëse Euroaziatike. Moska po përdor disa taktika të mënçura, duke sugjeruar edhe dhënien e aksioneve ndaj kompanive Evropiane, të përfshira në investimet e projekteve të ndryshme. Rusia, gjithashtu, përdor pushtetin e saj politik për të dekurajuar disa prej shteteve bregdetare të rajonit të Kaspikut, për të mos mbështetur planet e BE-së për shumëfishimin e furnizuesve të gazit.

Nga ana tjetër, për shkak të mungesës së infrastrukturës së përshtatshme, Azerbaixhani dhe Turkmenistani, nuk i përmbushin dot plotësisht kërkesat e BE-së, si dhe nuk ofrojnë aternativa të besueshme ndaj gazit Rus, në një afat të shkurtër kohor. Në planin afatgjatë, megjithëse rrugët e reja duke shmangur Rusinë janë duke u zhvilluar, kapacitetet e eksportit të këtyre dy vendeve bregdetare Kaspike, janë të pamjaftushme për t’u shndërruar në aktorë të fuqishëm lojë, për garantimin e energjisë ndaj BE-së. Përveç kësaj, Korridori Jugor i Gazit mund të sjellë konkurrencë për të gjitha vendet e BE-së dhe të mpijë Rusinë si “armë energjitike”.

Në të njëjtën kohë, Rusia ende mund të kërkojë të shfrytëzojë avantazhet ndaj kostove të saj, duke mbajtur larg tregut Evropian konkurruesit. Moska mund të vazhdojë të shes gazin me çmime të ulta, ndërsa sfiduesit e rinj, si për shembull tubacioni i gazsjellësit nga Turkmenistani, duhet të ofrojnë një çmim më të lartë që të kenë përfitime. Asnjëri prej vendeve, qoftë Azerbaixhani qoftë Turkmenistani nuk do të kenë avantazhe të ngjashme, dhe si rrjedhojë projektet e gazjellësit TANAP, TAP dhe Trans-Kaspik, nuk mund të zëvendësojnë aksionet e Rusisë në tregun e BE-së për gazin natyral. Duke marrë parasysh situatën aktuale financiare globale, shoqëruar me çmimet e ulta të naftës dhe të gazit, është e vështirë të konsiderohet transformimi i rajonit të Detit Kaspik në një nyje traziti për BE-në në të ardhmen.

Siguria e Energjisë së BE-së e mbërthyer midis Manovrës së re të Rusisë dhe Problemeve të Mbartura

Fusha e shahut shumë-dimensionale, e gazit natyror të Rusisë është lehtësisht e kuptueshme, teksa Moska ka shumë interesa ekonomike dhe gjeopolitike në gjirin e Detit të Zi dhe Kaspik. Ndërkohë që vendet e etura për energji të Evropës Jugore dhe Lindore, po përpiqen që të promovojnë TANAP dhe TAP, me shpresën e përshpejtimit të integrimit të tyre në sistemin energjitik Evropian, Rusia vazhdon të transmetojë sinjale të ndryshme, lidhur me linja të ndryshme të transportit të gazit. Pavarësisht, dozës së rëndë me sanksione nga Perëndimi, Moska ka çuar përpara qëllimin, për të ndërtuar një tubacion me Turqinë, duke pasur një kontroll potencial ndaj nyjës së gazit në kufirin Turko-Grek, për shitjet që do t’i bëhen Evropës.

Rusia dhe Turqia janë partnerë strategjik kyç për shumë vite. Që prej ardhjes në pushtet të Vladimir Putin dhe Rexhep Tayyip Erdogan përpara 15 vitesh, të dyja shtetet kanë krijuar një bashkëpunim të ngushtë, jo vetëm në sektorin e energjisë, por edhe në fusha të tjera, atë të tregtisë, turizmit, ndërtimit, prokurimit të armatimeve dhe investimeve të kapitalit. Inicativa më e fundit e Rusisë, e njohur edhe si “Turkish Stream”, paraqet mundësinë e bllokimit të të gjitha burimeve alternative të gazi, që vijnë nga Turqia për në BE. Nëse, Moska dhe Ankaraja miratojnë marrëveshjen e implementimit të këtij projekti, Turkish Stream paraqet ndërlikim serioze për disa prej Vendeve Anëtare të BE-së, në lidhje me shumëfishimin e furnizuesve të energjisë për në tregun Evropian. Në rast se, projeti implementohet në një afat të shkurtër, gjigandi Rus i energjisë Gazprom, lehtësisht mund të ulë çmimet e gazit krahasuar me kostot e larta të gazit Kaspik në tregun Turk dhe atë Evropian.

Turkish Stream, është një strategji e menduar dhe kalibruar më së miri, nga ana e Presidenit Putin, duke pasqyruar llogaritjet e reja gjeopolitike nga ana e Kremlinit si aksioneri më i madh në lojën Euroaziatike.

Ndërkaq, politika e Presidentit Putin, në lidhje me furnizimin e energjisë, në tregun Evropian duket e sigurt. Moska tashmë sfidon haptazi blerësit e së ardhmës të gazit nga Azerbaixhani, veçanërisht ndaj konsumatorëve, të cilët janë të lidhur direkt me projektin Turkish Stream. Në mungesë të një sfide Evropiane, më të bashkërenduar ndaj sigurisë së energjisë, koncepti i ri i Rusisë, lidhur me gazin ka për qëllim, të ndërtojnë fillimisht Turkish Stream dhe më pas, të pres për ndërtimin e infrastrukturës në Evropë. Ka të gjitha gjasat, se kjo lëvizje, do t’i mundësojë Moskës fitoren dhe t’i sjell shqetësime BE-së, lidhur me zgjidhjen e çështjeve aq të diskutueshme, të cilat mund të përcillen nga ana e konsumatorëve Evropian.

Megjithatë, mbetet interesant fakti se, disa prej vendeve bregdetare Kaspike, janë në gjendje të përdorin shkathtësinë e tyre, lidhur me çështjen e eksporti të energjisë. Për shembull,gjatë viteve të fundit, autoritetet drejtuese në Baku, kanë arritur të mbajnë një qëndrim diplomatik të ekulibruar, pavarësisht interesave gjeopolitike konkurruese, në gjirin e Detit të Zi-Kaspik, duke qenë se Azerbaixhani ofron furnizimin me energji jo vetëm, ndaj Turqisë dhe BE-së, por gjithashtu, edhe ndaj Rusisë dhe Iranit. Azerbaixhani nuk e konsideron Turkish Stream, si një projekt rival për Korridorin e Gazit Jugor. Në fakt, kapaciteti i Turkish Stream mund të përdoret nga Azerbaixhani, duke përdorur mundësinë e transportimit, falë zgjerimit të tubacionit gazsjellës Rusi-Turqi, nëpër territorin e Evropës, duke furnizuar me sasi shtesë të gazit natyror në të ardhmen.

Në të njëjtën kohë, Irani vendi i dytë në botë, që zotëron rezervat e gazit natyror pas Rusisë, do të rishikojë rrugët e ndryshme të eksportit për në Evropë, tani që sanksionet ndërkombëtare janë duke u hequr. Teherani, gjithashtu, mund të shfrytëzojë tubacionin e Turkish Stream, nëpërmjet njërës prej rrugëve të mundshme, nga ku gazi i Iranit në të ardhmen, mund të përçohet pranë konsumatorit Evropian. Paralelisht, marrëveshja më e fundit mbi programin bërthamore të firmosur në korrik e quajtuar P5+1, ka hapur mundësi të reja për zgjerimin e lidhjeve ekonomike ndërmjet Iranit dhe vendeve të tjera fqinje të Kaspikut. Në mënyrë të veçantë, Irani është duke kërkuar për rrugë të reja bashkëpunimi më të ngushtë me Azerbaixhanin, lidhur me eksportin e energjisë. Pasi ti jenë hequr sanksionet deri në Korrikun e 2016, Irani do të jetë në gjendje të përdor, tubacionin Baku-Tbilis-Ceyahan, me qëllim eksportin e naftës së vendit të tij dhe gjithashtu, do t’i bashkohet TANAP, për të transportuar gazin në Evropë në të ardhmen.

Megjithatë, ekzistojnë një sërë arsyesh, përse Irani ka pak gjasa që të eksportojë gazin e vendit të tij në Evropë në një afat të mesëm. Për shkak të situatës shqetësuese, mbi sigurinë në Turqi, ku infrastruktura mbi energjinë, përfshirë këtu, edhe tubacionin e gazit Iran-Turqi, është sulmuar në mënyrë të vazhdueshme nga organizatat terroriste, transportimi i gazit nga Irani për në tregun Evropian do të ishtë një zgjedhje jo e mirë për Teheranin. Pavarësisht se, Irani gëzon burime të shumta të gazit dhe nafës, investime të konsiderueshme dhe një tekonologji e re është e nevojshme, për të përpunuar rezervat e mëdha të energjisë në vend. E fundit por jo më pak e rëndësishme, ka të bëjë me distancat e gjata dhe kostot e larta të tranzitit, Evropa për momenin nuk është përparësia kyçe e Iranit, duke qenë se Irani është i përqëndruar, kryesisht në eksportin e gazit natyror ndaj vendeve fqinje.

Në mënyrë të spikatur, pasiguritë lidhur me Turkish Stream dhe Korridorin e Gazit Jugor, mund të vendosin mbi fatin e rrugëve, që do të ndjekin tubacionet. Megjithatë, mbetet për t’u parë, nëse të dy projektet do të pësojnë fatin e South Stream dhe Nabuccos. Gjithësesi, një gjë është tashmë e qartë: gjithëçka që ndodh sot me politikat mbi gazsjellësit në Euro-Azi, varet nga kërkësa e BE-së për energji në të ardhmen dhe lëvizjet strategjike të Rusisë.

Nga Erlet Shaqe

Pennine Petroleum Corporation announced that it has signed the main terms and conditions of a production sharing agreement for the Velca Block, in southern Albania, with licensee Albpetrol Sh. A. (“Albpetrol”), the national oil company of Albania.

Pennine Petroleum Corporation announced that it has signed the main terms and conditions of a production sharing agreement for the Velca Block, in southern Albania, with licensee Albpetrol Sh. A. (“Albpetrol”), the national oil company of Albania.